Erik Prince and the Privatized Empire of Exile

How Trump’s Favorite Mercenary Turned Immigration Enforcement into a Transnational Business

Erik Prince has never stopped waging war, only the battlefields have shifted. The founder of Blackwater, infamous for the 2007 Nisour Square massacre that killed 17 Iraqi civilians, built a $1 billion empire outsourcing violence, from Fallujah to Central America, per federal contract records. Once ousted from Pentagon circles after Blackwater’s scandals, Prince has reinvented himself as a security visionary for the global right, peddling solutions to border chaos. In 2025, under Donald Trump’s second administration, he’s the architect of a contractor-driven deportation regime, reshaping immigration enforcement.

Through 2USV LLC, Prince targets thousands for El Salvador’s CECOT mega-prison, a 10,000-bed facility proposed as “U.S. territory” to evade oversight, per Politico. Enabled by biometric surveillance, like ICE’s $150 million systems, Trump’s deportation policies risk errors like Kilmar Abrego Garcia’s 2025 deportation to CECOT. Trump’s vow to deport “homegrown criminals” abroad and invoke the Alien Enemies Act fuels fears of overreach. Prince’s security deals in Haiti and Ecuador, deploying mercenaries against gangs and cartels, extend his contractor-driven model, mirroring a 2025 proposal to privatize U.S. deportations.

This investigation traces Prince’s rise from wartime profiteer to deportation czar, exposing how, under “security’s” guise, the U.S. exports outsourced enforcement and paramilitary force to Latin America, threatening human rights worldwide.

Origins of a Mercenary Mogul

Erik Prince’s empire took root not in El Salvador’s jungles but in the warzones of Iraq and Afghanistan, where he turned conflict into a 21st-century fortune. In 1997, he founded Blackwater USA in North Carolina as a training hub for Navy SEALs and security personnel. The 2001 Afghanistan and 2003 Iraq invasions transformed it into a private army, amassing ~$1.2 billion in U.S. contracts by 2007, including a $27 million no-bid deal to guard Iraq’s U.S. administrator, Paul Bremer, according to the House Oversight Committee.

Blackwater’s 20,000 ex-military operatives, notorious for aggressive tactics, ignited global outrage in 2007’s Nisour Square massacre, killing 17 Iraqi civilians. The incident led to Iraq’s temporary contractor ban and 2014 convictions of four guards, sentenced in 2015. Prince rebranded Blackwater as Xe in 2009, then Academi in 2011, sidestepping its toxic legacy.

Undeterred, he expanded globally, brokering Somalia anti-piracy deals and pitching Venezuela regime-change plans by 2019. His 2011 UAE contract, worth $529 million, built an 800-strong foreign legion of Colombian and South African fighters to suppress dissent. Prince thrived just beyond legal reach, a borderless security tycoon.

The Trump era revived his U.S. influence. In 2020, Trump pardoned the Nisour Square operatives, signaling private force’s return to American power. This absolution cleared Prince’s path to 2025, where his outsourced warfare empire would target new frontiers.

From Desert Wars to the Deportation Complex

As the war on terror faded, Erik Prince pivoted his empire to immigration, exploiting new battlegrounds in 2025. With Donald Trump’s second administration wielding the Alien Enemies Act to militarize borders, Prince’s contractor-driven warfare found eager demand. His 2USV LLC proposed a vast deportation apparatus, targeting thousands of migrants and detainees for offshore prisons, Politico revealed. Trump’s April 2025 hot mic urging El Salvador’s Nayib Bukele to build “five more places” for “homegrown criminals” hints at U.S. citizen deportations, Newsweek reported, amplifying fears of overreach.

The plan centers on a 10,000-bed detention camp within El Salvador’s CECOT mega-prison, holding 40,000 inmates in 0.6 square meters each, with 368 deaths, Amnesty International reports. Politico details 2USV’s contracts to manage the camp with 150+ American and regional contractors, paying bounties for capturing undocumented individuals—a privatized deportation force. El Salvador’s “U.S. territory” designation for the camp bypasses U.S. due process and treaties like non-refoulement, creating a jurisdictional void.

Surveillance fuels this scheme. Palantir’s tools, generating leads for ICE deportations via real-time data integrations, could empower 2USV’s hunts, 404 Media’s leak suggests, though direct ties remain unconfirmed. Kilmar Abrego Garcia’s 2025 deportation to CECOT, exposes systemic risks. Unverified claims of deporting 100,000 U.S. inmates, pitched to officials, highlight the plan’s ambition. Trump’s rhetoric, vowing to exile “homegrown criminals,” further escalates concerns. From Baghdad’s warzones to Latin America’s barrios, Prince’s empire monetizes fear, evading oversight with every contract.

The Mechanics of Exile: Prince’s Deportation Machine

Erik Prince’s 2025 venture is a chilling infrastructure, unaccountable to courts, press, or public. Prince’s 2USV LLC seeks contracts to operate the 10,000-bed detention camp within El Salvador’s CECOT mega-prison, as “U.S. territory,” an offshore Guantánamo evading U.S. oversight.

The model fuses high-tech surveillance with brutal tactics:

Contractor-led bounty hunters, paid per capture, track undocumented migrants.

Private security, with 150+ U.S. veterans and regional recruits, guards and transports detainees.

Mass relocations of thousands align with Trump’s 2025 immigration mandates.

The “U.S. territory” designation sidesteps constitutional protections, enabling indefinite detention.

Critics liken it to extraordinary rendition, with ACLU lawyers warning of mass due process violations—no counsel, rampant abuse, and breaches of non-refoulement. Trump’s rhetoric, vowing to deport “homegrown criminals” abroad, fuels fears of overreach, though Senator John Kennedy’s unconstitutional claim remains unverified. Kilmar Abrego Garcia’s 2025 deportation to CECOT, a legal U.S. resident misidentified by contractor haste, amplifies these dangers.

Logistics are opaque, but surveillance tech drives the machine. Palantir’s tools, generating ICE deportation leads via real-time data, could enable 2USV’s hunts. With ICE’s $150 million systems tracking biometrics, Prince’s scheme thrives beyond government control. If approved, this camp isn’t an outlier—it’s a blueprint for contractor-driven exile, scaling Blackwater’s impunity to borders.

Bounty Hunters for Hire: 2USV’s Deportation Force

Erik Prince’s 2USV LLC seeks to supplant ICE’s enforcement with a contractor-driven deportation force, operating with scant oversight. Investigations reveal 2USV’s plan: a network of 150+ bounty hunters—U.S. veterans and regional recruits—paid per capture to track, detain, and deport undocumented migrants. Modeled on Blackwater’s paramilitary raids, these operatives will target thousands for El Salvador’s CECOT mega-prison, a facility marked as “U.S. territory” to evade constitutional limits.

The logistics are starkly efficient. 2USV taps federal surveillance, leveraging biometric data and facial recognition from ICE’s Enforcement and Removal Operations (ERO) database. Palantir, managing ERO under a $150 million contract, enables real-time targeting. This digital backbone, generating leads via ICE’s Investigative Case Management system, sidesteps judicial review for swift relocations, bypassing traditional hearings. Claims of plea deals to waive appeals lack evidence, but Politico describes a pipeline governed by contracts, not law.

El Salvador’s role is pivotal. President Nayib Bukele partners with Prince for a $6 million deal to host U.S. deportees, mutliple sources have confirmed. A 2025 letter from El Salvador’s justice minister names 2USV a “trade agent,” granting operational freedom. The stakes are grim. Amnesty International flags CECOT’s torture-like conditions—no counsel, isolation—as violations of non-refoulement. ACLU critics label this a modern extraordinary rendition, per 2025 statements, empowering 2USV as judge, jury, and jailer.

2USV’s model isn’t a fix—it’s a crisis machine. This bounty-driven blueprint, profiting from exile, reshapes U.S. immigration enforcement into an unaccountable, scalable regime, extending Prince’s impunity from warzones to borders.

El Salvador as a Legal Black Hole

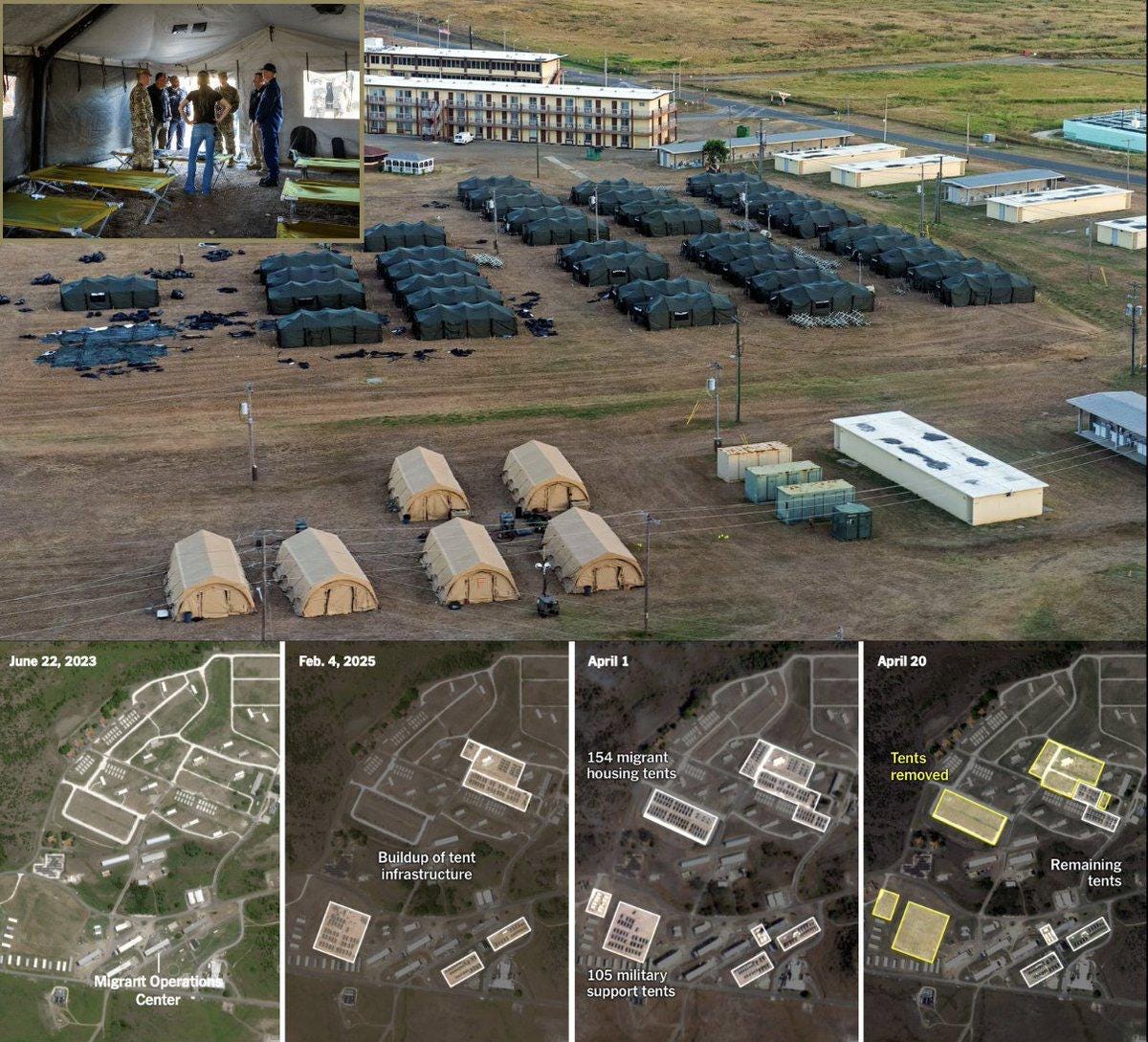

El Salvador anchors Erik Prince’s deportation empire, a legal and technological crucible for contractor-driven punishment. A proposed Treaty of Cession would designate the 10,000-bed camp within CECOT mega-prison as “U.S. territory,” stripping detainees of legal protections from either nation. This rights-free zone, run by 2USV LLC, mirrors an offshore Guantánamo, evading accountability. A precursor emerged in 2025, when Trump’s DHS built a $40 million tent city at Guantánamo to hold 30,000 migrants, as we reported, only to dismantle it by April after detaining just 497, costing $80,000 per person, with deportations to El Salvador under legal scrutiny for violating court orders.

Nayib Bukele’s surveillance-heavy regime, leveraging facial recognition, biometric databases, and deals with Google and Bitcoin firms, fuels this dystopian experiment. Bukele is effectively renting out CECOT cells, hosting 238 U.S. deportees for $6 million under a “one-year renewable” term, KQED reported, with a 2025 justice ministry letter naming 2USV a “trade agent.” Allegations of U.S. influence over Bukele have long persisted, but 2025 reports identify Ronald Johnson as his alleged CIA handler. Johnson, confirmed as U.S. Ambassador to Mexico on April 9, 2025, with a 49-46 Senate vote, The New York Times reported, built a tight partnership with Bukele during his El Salvador tenure, focusing on migration and security. A former Army Green Beret with decades in Latin America, Johnson received El Salvador’s highest diplomatic honors, Latin Times noted. His 2025 Mexico role coincides with Trump designating Mexican cartels as “Terrorist Organizations,” suggesting a U.S. strategy to militarize border policies potentially linked to CECOT’s expansion. Johnson’s military background, including decades in the U.S. Army National Guard and Special Forces across Latin America, positions him as a likely conduit for U.S. policy, possibly facilitating Bukele’s $6 million deal.

Trump’s hot mic urging Bukele to build “five more places” for “homegrown criminals,” signals further growth, echoed by DHS chief Kristi Noem’s 2025 CECOT tour lauding its model—months after inspecting Guantánamo. CECOT’s conditions violate non-refoulement, potentially breaching the Leahy Law against U.S. aid to abusive forces, despite $6 million allocated. El Salvador isn’t just a hub; it’s a prototype for extraterritorial repression, scalable wherever sovereignty bends to capital.

Haiti, Ecuador, and the Broader Theater

El Salvador’s CECOT camp is Erik Prince’s prototype, but his ambitions span a network of mercenary-led control across Latin America. As states falter, 2USV LLC exploits crises in Haiti and Ecuador, entrenching U.S.-aligned ventures fueled by profit and impunity, extending the “Treaty of Cession” model.

In Haiti, where gangs outnumber the Haitian National Police 15,000 to 3,500 and control 80% of Port-au-Prince, Prince’s contract deploys mercenaries to advise the government, Latin Times reported. Armed with weaponized drones and a large shipment of weapons, they conduct lethal operations to repel gangs threatening to take the capital, risking extrajudicial killings reminiscent of Blackwater’s Iraq abuses. Prince is recruiting Haitian American veterans like Rod Joseph, a U.S. Army Purple Heart recipient who ran for office in 2024, per Ballotpedia, confirming his strategy to leverage local legitimacy. The State Department denies funding Prince, highlighting the privatized nature of this intervention. Haiti’s collapsed state mirrors Prince’s African playbook: crisis breeds dependency on private force, with 2USV poised to dominate.

In Ecuador, President Daniel Noboa, re-elected in April 2025, escalated his anti-cartel crusade amid 1,500 homicides in early 2025. Born in Miami and educated at NYU and Harvard, Noboa’s U.S. ties have sparked allegations of being an “American plant” with potential CIA connections, mirroring Bukele’s dynamic in El Salvador. After prison riots in 2024, Noboa declared an “internal armed conflict,” welcoming Prince’s support. A March 2025 meeting led 2USV to offer security training and raids in Guayaquil, though ongoing talks for “technical support” lack confirmation of CECOT-style detention centers. Biometric surveillance, akin to ICE’s $150 million systems, could guide 2USV. Noboa’s approach tests mercenary-led repression in Quito’s barrios, raising questions about sovereignty.

These ventures amplify El Salvador’s risks, where 2USV’s bounty hunters feed CECOT’s pipeline. Kilmar Abrego Garcia’s deportation to CECOT, detained due to biometric mismatches, underscores legal voids. U.S. backing, evident through Ronald Johnson’s influence over Bukele, emboldens Prince’s operations in Haiti and Ecuador. Haiti’s gang wars and Ecuador’s violence offer fertile ground for 2USV’s expansion.

Prince’s model, rooted in UAE ($529 million) and African operations like training 2,000 Somalis for anti-piracy in 2011, hints at replication in unstable regions like Eastern Europe, though no plans are confirmed. His May 2025 commitment to speak at African Energy Week in Cape Town, per the African Energy Chamber, signals continued focus on Africa’s crises, potentially extending his empire of exile. Like post-9/11 U.S. basing, he exploits instability for permanent infrastructure, claiming security mandates. Accountability vanishes: Prince skirts Congress, framing mercenary work as aid. This apparatus fuses counterinsurgency with immigration policy, embracing legal liminality. From Port-au-Prince’s slums to Guayaquil’s streets, Prince’s empire grows—one contractor-led crackdown at a time, threatening human rights across borders.

Letters of Marque for the Modern Age

The age of privateers is returning—but the targets aren’t enemy ships. They’re migrants, cartel members, and anyone deemed a “national security threat” by algorithm or decree. Erik Prince, leveraging his history of mercenary ventures and proximity to the White House, is reviving the concept of letters of marque for a new era: a legal framework to authorize privatized enforcement beyond public accountability.

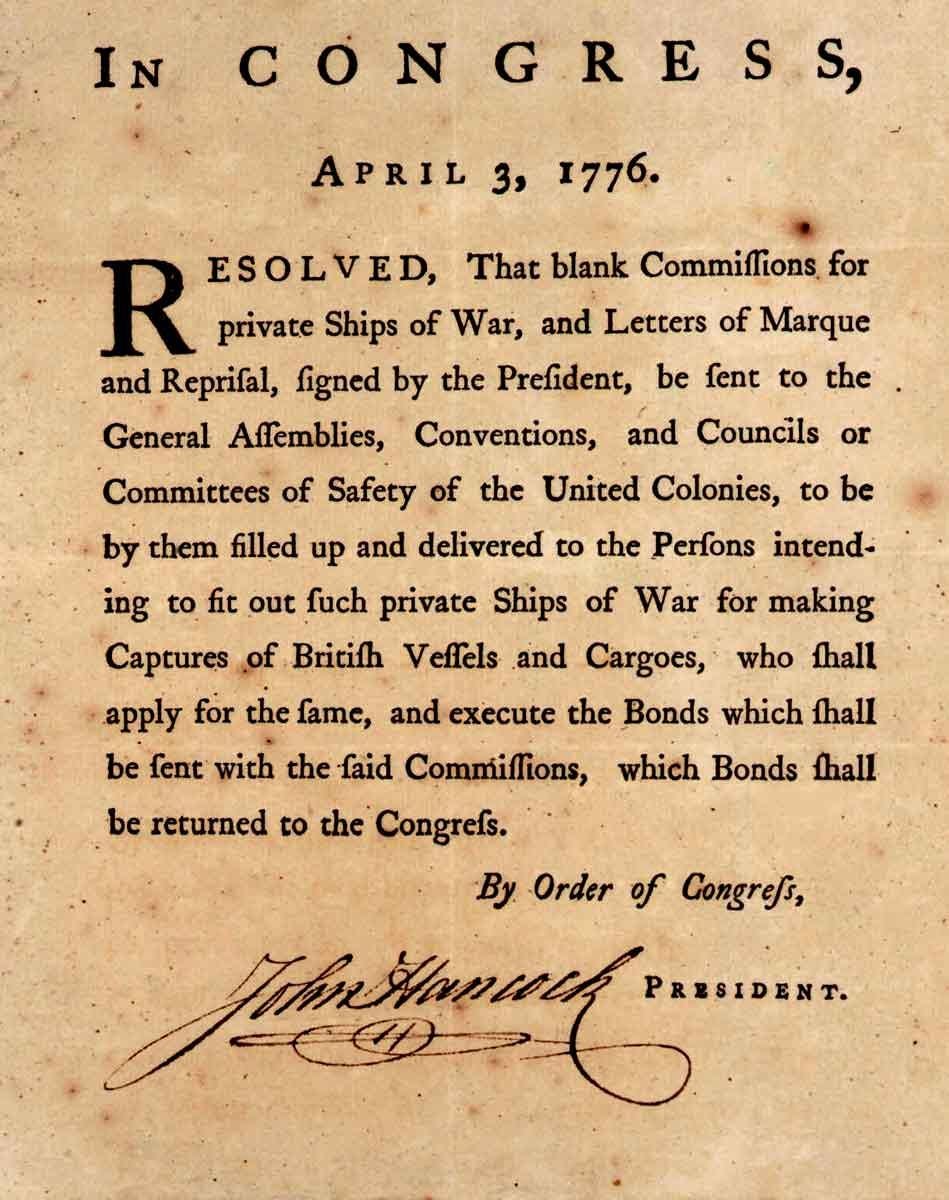

Historically, letters of marque were government licenses allowing private citizens to wage war on behalf of a state, often targeting enemy vessels. Letters of Marque and Reprisal, often abbreviated as "Letters of Marque," were government-issued documents that authorized private citizens to seize property from foreign parties, effectively turning them into privateers. These letters, granted during wartime, were a way for nations to leverage private ships and individuals to harass or attack enemy vessels and property. Is the United States at war?

Prince is pushing a modern equivalent, seeking legal immunities that would allow private contractors to act in semi-sovereign roles against drug cartels and migrants. Prince pitched the White House on outsourcing mass deportations, a plan that included operating in lawless zones like El Salvador’s CECOT. Insiders suggest Prince and affiliated groups are lobbying for a framework—informally dubbed the “Border Privateer Act”—to shield contractors from liability in contested regions, treating cartels as enemy combatants with battlefield rules of engagement on foreign soil, modeled on post-9/11 counterinsurgency carveouts.

Trump’s rhetoric supports this shift. In 2025, he effectively declared war on cartels by designating them “Terrorist Organizations,” a stance backed by tensions over potential U.S. military strikes. This framing—cartels as wartime enemies—lays the groundwork for legalizing cross-border, privatized enforcement. Prince, who has advised Trump’s administration on security, per Politico, stands to gain a mandate to operate with impunity.

Critics warn this creates a parallel military with no democratic oversight. As seen in Haiti, Ecuador, and El Salvador, Prince’s forces already exploit zones of legal ambiguity. Formalizing this through modern letters of marque would codify the state’s abdication of sovereignty to contractors. Tech firms like Palantir amplify the risk: their AI tools, used for predictive policing in New Orleans since 2018, per The Verge, could generate “target lists” for migrants or cartel members. If outsourced to armed contractors, this shifts from border security to privatized warfare, enabled by digitized decrees.

Prince isn’t just seeking contracts—he’s seeking a mandate to reshape enforcement. In a political climate where Trump’s base demands action on migration and cartels, Prince may find the support he needs to turn his vision into policy, threatening accountability and human rights on a global scale.

Legal and Ethical Collapse

Erik Prince’s privatized immigration regime, through 2USV and CECOT, systematically dismantles the legal boundaries defining state power, evolving into a transnational experiment in extrajudicial punishment that violates U.S. constitutional guarantees and international human rights law.

Domestically, the U.S. Constitution guarantees due process to all persons, not just citizens, and the Eighth Amendment bans cruel and unusual punishment. Yet Prince’s contractor-led system strips individuals of legal standing, as seen with wrongful deportations to CECOT, where inhumane conditions defy constitutional protections. In these offshored detention zones, U.S. oversight drives the system, but constitutional rights are left behind.

Internationally, this regime breaches treaties the U.S. has ratified. The UN Convention Against Torture (Article 3) prohibits returning individuals to places risking torture—non-refoulement—a principle CECOT violates, per OHCHR. The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (Article 10) mandates humane treatment for detainees, and the Mandela Rules ban indefinite detention without counsel—standards Prince’s facilities ignore. By reclassifying deportees as “extraterritorial detainees” under the Treaty of Cession, the Trump–Prince axis—evident in Trump’s 2025 cartel war declaration, evades these obligations, flouting both international and domestic law.

This erosion is deliberate, built on systems outlined earlier: surveillance tools feeding 2USV’s dragnet, bounty systems incentivizing removals without oversight (Section V), CECOT as an offshore engine of impunity, and a model exported to Haiti, Ecuador, and Mexico’s proposed cartel war. Together, they form a contractor-run apparatus where accountability vanishes.

What emerges is a shadow legal regime, crafted through lobbying, executive fiat, and commercial contracts, bypassing Congress and the judiciary. This architecture echoes the post-9/11 extraordinary rendition system, but now targets migrants and scales globally. In abandoning legal norms for contractual convenience, the U.S. isn’t just delegating enforcement—it’s privatizing impunity, threatening the foundations of justice and human rights.

The Shadow Expands

Erik Prince’s empire of exile—from El Salvador’s CECOT to Haiti, Ecuador, and beyond—has birthed a new paradigm: enforcement as a for-profit enterprise, unbound by law or morality. The investogation has laid bare the legal and ethical collapse, but the reality is grimmer: those who enable Prince, from Trump to complicit leaders like Bukele and Noboa, thrive on this impunity. In 2025, 261 Venezuelan deportees vanished into CECOT, per Amnesty International—their stories erased, their families left in anguish. This is the human toll of a system designed to profit from disappearance.

There’s little hope in petitioning the same U.S. politicians who greenlit this regime. Trump’s 2025 cartel war declaration, shows the political class’s appetite for privatized solutions, not accountability. Prince’s vision is already scaling—his DRC deal and African Energy Week engagement signal a global blueprint. Any crisis zone could be next, as he exploits instability for profit.

This isn’t a problem for Congress or the UN to solve—it’s a warning. Prince’s shadow legal regime is a glimpse of a future where justice is a commodity, sold to the highest bidder. We can’t rely on broken systems to fight back. Will we accept this dystopia—or find ways to resist before the shadow consumes us all?